If A Complete Unknown Is Your Entry to the 1960s Folk Revival,...

you heard CORE mentioned, and you want to learn more about the intersection of the Civil Rights Movement and Folk...

Around 2006 or so, my dad and I drove to Milwaukee from Chicago for a Bob Dylan concert. I remember our excitement driving north on 294 as we listened to the Bob Dylan mix cd I made for the ride. In short, the concert was disappointing. Bob Dylan rearranged all of his songs, so that they were unrecognizable—the band was just loud and harsh—not in a Sonic Youth way but more in a newly formed middle school band way. Dylan is notorious for this, but we were pissed. Unlike the Newport 1965 audience depicted in A Complete Unknown, we didn’t boo. Just sulked.

By that time, I had become a mirror of my dad’s interests, which included 1960s folk music. My dad bought his first guitar at 16, then finally bought his first high quality guitar at 21. It was a Martin D35, a classic spruce acoustic guitar with a warm tone—-Johnny Cash and Jim Croce played on D35s. Bob Dylan, Neil Young and Joan Baez all played on similar Martin models. I grew up listening to my dad play folk music on that guitar. He had me listen to Peter, Paul and Mary and Baez duets with Dylan, in the hopes that I too would understand how to harmonize. I wish I had been able to see A Complete Unknown with my dad because I can’t think of anyone else I know who would’ve been excited about the references that were meaningful to me in the film. To be clear, it’s not a profound movie or really one that encourages deep thinking, at least not unless you already have some insight. Arguably, I’m Not There does a better job telling the same story. Cate Blanchett and Marcus Carl Franklin played superior Dylans, in my opinion. Still, I found many of the film’s references delightful, so I thought that I’d kind of ramble, as I do, through those references that I don’t get to talk about with my dad. Of course the film was a super fictionalized and hollywood-ized version of the time period (I’m pretty sure Johnny Cash wasn’t at Newport in 65 crashing into people’s cars or even there). I’m not a complete expert, but I have spent most of my life immersed in the intersection of music and social movements.

As I wrote about previously, I believe that artists have somewhat of a duty to make sociopolitical art and to be engaged in social justice movements in these dark times. The folk revival, of which Dylan was a part and is portrayed in the film, was a part of the freedom movements of the 1960s. While the film inevitably shows that intersection, I’m not sure the filmmakers really understood what this meant completely or perhaps they did and were uninterested in telling that story, that is in part about class warfare. The character Sylvie (a fictionalized Suze Rotolo) briefly mentions volunteering at CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) to aid in The Freedom Rides coordination (The Freedom Rides were a direct action campaign to desegregate interstate bus travel in 1961. The rides began with CORE, KKK and other white supremacist violence escalated against the riders, including fire bombed buses, and John Lewis was famously beaten. Then SNCC, led by 23 year old Diane Nash, took over and spent the subsequent months riding to Mississippi and becoming imprisoned in Parchman Prison as they refused to pay bail, rendering the state’s power useless against them). Many audience members will surely miss this because Elle Fanning says it so quickly. I believe it was Dylan’s relationship with Rotolo that introduced him to the Civil Rights Movement, and this is alluded to in the film when Dylan asks Sylvie what CORE is.

This is significant because some of my favorite songs from the Movement were written by Dylan—

“The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”

“The Death of Emmett Till”

“Only a Pawn in Their Game” (This song is about Medgar Evers, and Dylan performed it at the March on Washington. Some didn’t approve, as the song opines that Evers’ murderer is a pawn in the broader goals of capitalism. I always taught this song as a teacher and had kids annotate it as they would poetry. Students typically agreed with Dylan’s messaging, as do I. I have some brilliant 6th grade annotated lyrics for anyone interested).

“The Times They Are a Changing”

“I Shall Be Free No. 10”

“With God on Our Side”

“When the Ship Comes In”

People criticize Dylan for various reasons, during various periods in his long career, but these were all original, poetic, complex civil rights songs. I can’t think of a contemporary artist who devotes so much of their craft to uplifting social movements.

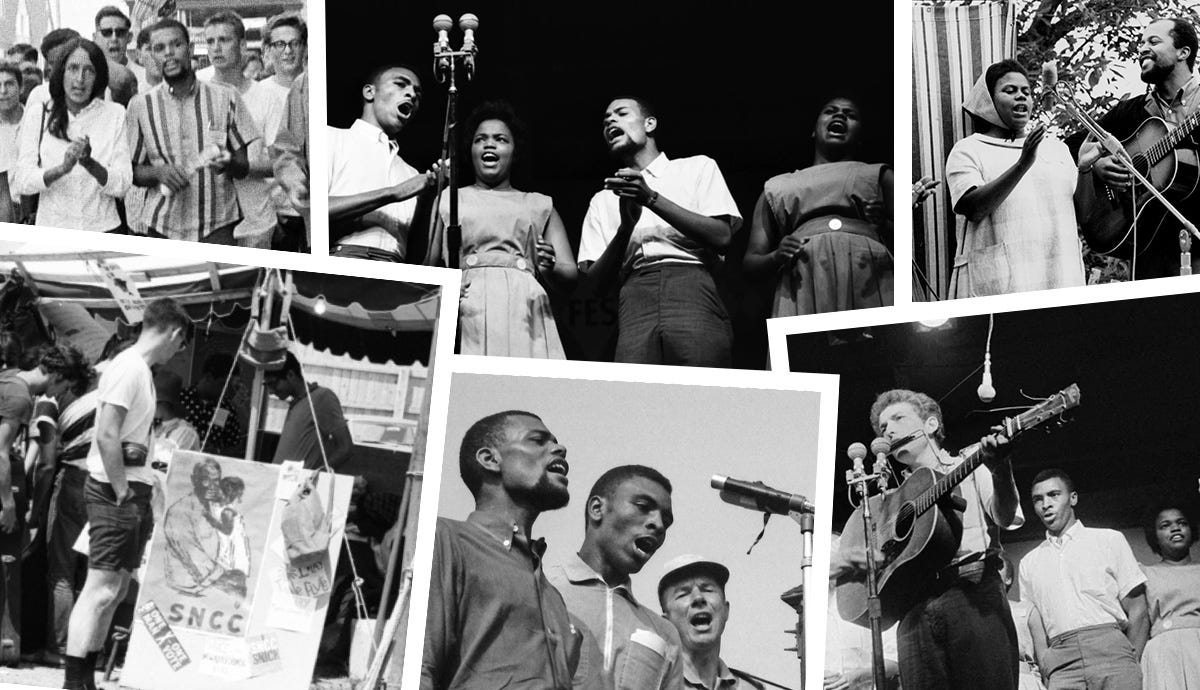

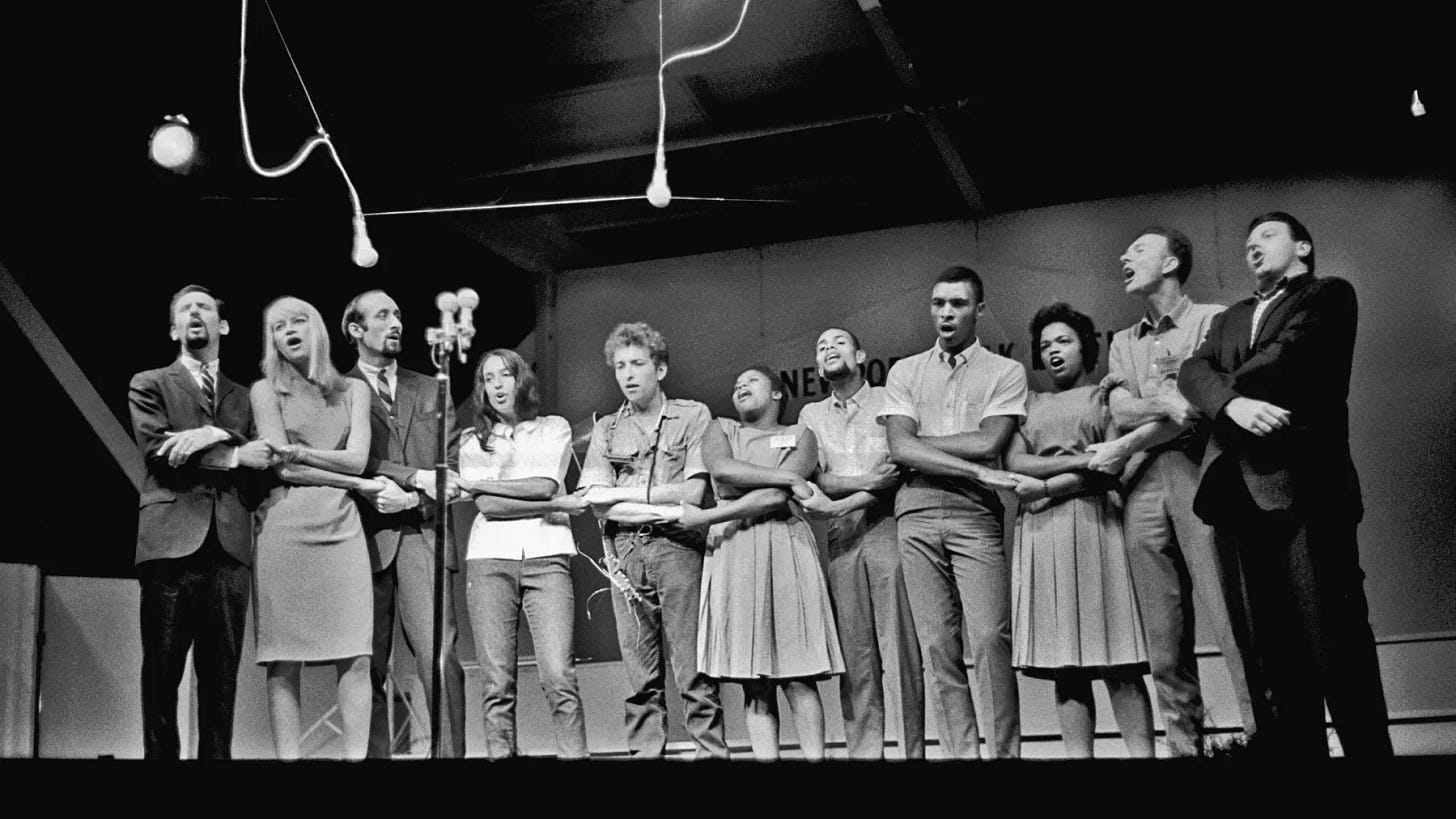

Before the film’s climax at Newport Folk in1965, Dylan first performed at the Newport Folk Festival in 1963. He was joined on stage for a rendition of “Blowin’ in the Wind,” by the SNCC Freedom Singers (including my dear friend Charles Neblett, who was still singing with me when I saw him just in October ‘24 at age 86) and the late Bernice Johnson Reagon, founder of Sweet Honey in the Rock), Joan Baez, Pete Seeger and Peter, Paul and Mary. Now, Chalamet’s Dylan might talk shit about this song in the film, and a cynical 2025 viewer might feel similarly, but the context is important and missing from the film—it wasn’t a silly song. “How many years can some people exist before they’re allowed to be free?” was a real question in 1963, not even 100 years after the abolition of chattel slavery; Just 8 years after Emmett Till was brutally beaten and tortured to death in 1955; Bob Moses had met Amzie Moore in Mississippi two years prior in 1961 and had just begun to build SNCC’s voter registration organizing program in the Deep South; Dr. King had just written “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” in April of that year; Bull Connor’s police were televised shooting powerful hoses and siccing dogs on children in Birmingham two months before Newport; Medgar Evers was gunned down in his driveway just a month before Dylan linked arms with the SNCC Freedom Singers, who were also community organizers. Charles Neblett by that point had been arrested countless times, worked at desegregating pools in his hometown of Cairo, Illinois and had been met with countless incidents of racist violence— “how many ears must one man have before he can hear people cry?”

Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan didn’t just kick around Beacon and Manhattan, as depicted in the film, but in 1963, the same year as Dylan’s first Newport and the March on Washington, Dylan traveled to Greenwood, Mississippi with Pete Seeger to perform at a SNCC voter registration rally where SNCC was organizing Black, mostly poor potential voters. This is the story that needed to be told.

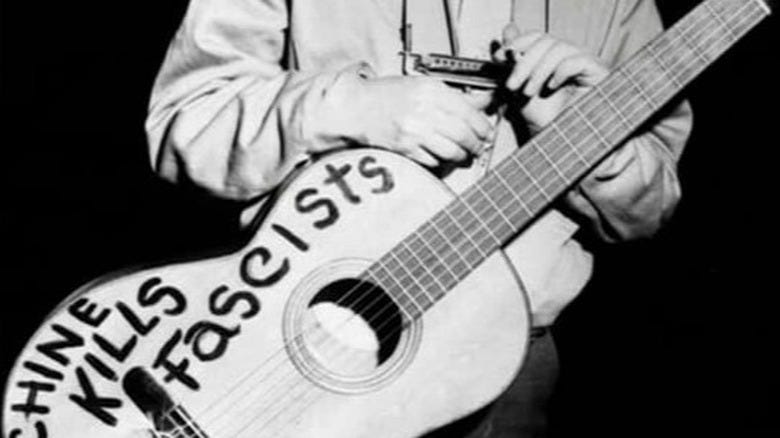

The tension portrayed in the film is one between acoustic and electric, folk purity and selling out, and Chalamet in a press tour calls Dylan something like the first punk rock figure in American culture and to me this misses the crux of what the folk revival scene was about—it was about building a community between organizers, activists and artists. The music was stripped down so that people could hear the messages in the songs. You can’t tell me Woody Guthrie wasn’t punk. I’ll come back to that…

Let’s talk about the portrayal of Pete Seeger—apparently there’s controversy surrounding his reaction to Dylan at Newport ‘65, and he didn’t want to cut Dylan’s performance off, but rather wanted to cut the distortion to better hear his lyrics. Who knows. It doesn’t matter much to me. What we do know is that Pete Seeger was a lifetime leftist activist, sometimes communist and organizer up until his death at 94 in 2014. In the film, he’s portrayed as a folk purist (Peter Yarrow too, and in my opinion his was the best physical casting). However, I think Seeger was driven more by his commitment to the causes—socialism, pacifism and anti-racism than a commitment to those D, A, G acoustic folk chords. Pete Seeger and Joan Baez for example, both supported Occupy Wall Street in 2011. By then, Baez was in her 70s and Seeger in his 90s. They never stopped their activism. The character, Sylvie, is wrong in the film—Pete Seeger’s song, “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” is beautiful and tragic and timeless. The wars haven’t ended. Seeger’s lifetime commitment to activism and creating principled art is admirable. This is certainly true of the socialist and union supporter Woody Guthrie too. Guthrie and Seeger formed the Almanac Singers in 1941, which was a pro-union, anti-fascist, pro-civil rights group. Guthrie was politicized unlike Seeger who grew up in a progressive family in NYC. Guthrie grew up in a racist family in Oklahoma and traveled across the country during the Dust Bowl, witnessed struggle and became immersed in the communist party and other workers’ movements. Please add “Tear the Fascists Down” to your inauguration playlists— “It’ll be the union that tears the fascists down.” Then listen to his “Deportees” if you still need a call to action. It makes sense that a Hollywood film waters down this history considering the legacy of McCarthyism that plagued Seeger and Guthrie’s lives and is still with us today.

The film also introduces some background musicians that deserve some extra research and listening—the first, I’ve mentioned, Peter, Paul and Mary. My dad was in love with this group. I recently read Will Hermes exceptional Lou Reed biography, and apparently Reed and many others thought Peter, Paul and Mary were corny. I did too as a middle schooler really into punk and hip hop. They mainly sang folk covers, but when Mary was still alive, I saw them countless times as a child, and in retrospect, they were not corny—their harmonies were beautiful, as was the guitar playing, there’s intricate finger picking, and again, they committed their art to struggle for their careers. There’s nothing corny about singing about radically imagining peace. Plus, their version of “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” is the most beautiful, and I prefer it to Dylan’s. You should probably listen to all of their 1963 album, In the Wind. Sheesh.

Odetta is seen backstage in the film as Dylan plays “Maggie’s Farm.” I love Odetta, and her contribution to civil rights through song should be recognized more than it is. She didn’t speak in this film, but she wasn’t in the background of the Movement. 1960s Folk was inspired in part by the blues, and Odetta’s blues voice with that folk guitar made her “the voice of the Civil Rights Movement.” I’m sure she influenced Joan Baez—you hear it in her vibrato. Dylan has said that she influenced him to sing folk and to pick up an acoustic guitar after he heard her record. Damn, I love her version of Dylan’s “With God on Our Side.” The guitar arrangement is spectacular. I’m not really a guitarist, but I’m going to say she has to be one of the best guitarists of all time if there’s a list somewhere.

I think the film’s delta blues musician was made up, but they did mention Lead Belly. Ugh, Hollywood and Black characters….anyways, Dylan was also influenced by Lead Belly—you hear it in Dylan’s amalgamation of folk and blues. If you’ve never heard a 12 string guitar, this is the way to hear a 12 string guitar.

And then finally, Toshi Seeger. She was a background character in the film too, and she barely spoke. She was posited as “the wife.” She wasn’t just Pete Seeger’s wife. She helped start Newport Folk, was a filmmaker and fellow activist too. I guess they showed her with a camera, but I recently learned that she made this short film about Black chain gang singers in Texas…very Alan Lomax. Speaking of whom, might I suggest a break from scrolling Tik Tok, to scroll through Lomax’s digital archive. Incredible stuff.

Bob Dylan continued writing what I would consider left leaning and prolific lyrics even after he went electric and was hanging around Andy Warhol and the Factory scene of the mid/late ‘60s… “Hurricane,” “George Jackson,” and more subtly songs like “Trouble” come to mind. He wrote some great songs, sometimes made more famous by others (“All Along the Watchtower,” made famous by Jimi Hendrix, “It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Bleeding,” made famous by the Byrds in Easy Rider).

All this to say, I enjoyed the film and thinking about its references, and of course the music, (both pre and post Highway 61 Revisited) and as always, it served as a reminder that Hollywood is not capable of telling radical, socialist, working class history with fidelity. Just impossible for that big ol’ propaganda machine. I suppose we at least get a glimpse.

I am enjoying this reminder to listen to Odetta and her peers. There’s so much Movement music out there from that time period—Phil Ochs, Nina Simone, John Prine…let me know if you want me to make you a playlist—as we head into a big year, let’s hope that our contemporary faves follow their lead.

Thanks for this terrific article. There’s a great performance by Bob of Hattie Carroll on the Steve Allen show in 1965, you can find it on YouTube if you haven’t seen.

Yes please publish a playlist!